Think the movie is the main event? Think again. The modern blockbuster isn’t just a film; it’s a meticulously planned, multi-billion-dollar marketing blitz designed to conquer your wallet long before you even buy a ticket. The movie has become the high-gloss, two-hour commercial for the real product: the merchandise.

Last year, you couldn’t escape the pink tidal wave of Barbie. It wasn’t just a movie; it was a cultural takeover. From Gap apparel and NYX makeup to Burger King meals and a real-life Airbnb Dreamhouse, Mattel and Warner Bros. executed a masterclass in pre-release dominance with over 165 brand partnerships. By the time the film hit theaters, buying a ticket felt like the final step in a months-long event you were already part of. This wasn’t an accident. It’s the new playbook.

From Candy Bars to Death Stars: The Revolution

This all started small. In the early days of cinema, product placement was often a happy accident or a cheap way to get props. A Hershey’s bar in the 1927 Oscar-winner Wings was a novelty. For decades, Disney was the only one who truly got it, turning Mickey Mouse into a merchandising empire to fund its expensive animations.

Then, in 1977, George Lucas changed the game forever.

In a legendary move, Lucas took a pay cut on Star Wars in exchange for the merchandising rights—something the studio saw as worthless. The result? A tsunami of toys, lunchboxes, and action figures that created a revenue stream more powerful than the Death Star. When demand outstripped supply, Kenner famously sold empty boxes with an IOU for future toys, and kids couldn’t get enough. Star Wars proved the toys weren’t just tie-ins; they were a business that could dwarf the box office.

A few years later, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) cemented the strategy when sales of Reese’s Pieces skyrocketed 65% after the alien was lured by the candy, sending a shockwave through corporate America. The modern blockbuster machine was born.

The New Playbook: Cultural Saturation

Today, the Star Wars model is on hyperdrive. Studios don’t just sell products; they build entire worlds for us to live in before the premiere.

The strategy is a “breadcrumb” campaign of staggered reveals that builds a constant hum of hype. It’s a force-multiplier, leveraging the marketing budgets of hundreds of partners to achieve a level of cultural saturation the studio could never afford on its own.

We saw it with Barbie‘s pink-pocalypse and again with Wicked (2024), which followed the exact same script with its green-and-pink aesthetic splashed across more than 70 brands, from LEGO and Crocs to Swarovski crystals. These campaigns transform a film release into a can’t-miss cultural event.

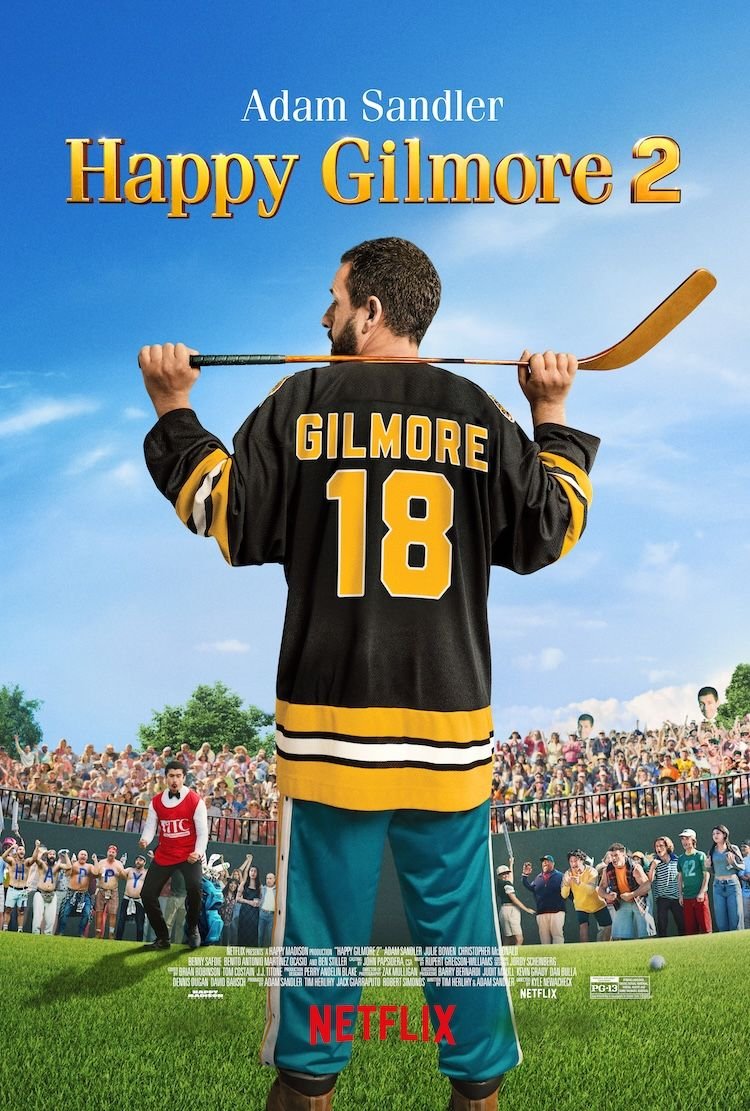

And don’t think this is just for theaters. Netflix is all in. The upcoming Happy Gilmore 2 (2025) is getting the full blockbuster treatment. This isn’t just about t-shirts; it’s about deep, functional integration into fans’ lifestyles. Golf giants Callaway and Odyssey have partnered with Netflix to release a line of high-end, movie-themed gear. You can buy a limited-edition replica of Happy’s iconic hockey-stick putter for $499.99 or play with golf balls stamped with classic quotes like “Just tap it in.” Add in partnerships with Subway and U.S. Bank, and it’s clear: even straight-to-streaming releases are now launchpads for massive consumer product empires.

The Dark Side of the Deal

But this relentless commercialization has a dark side. When does a cultural event become “heavy-handed culture-jacking?” Critics of the Wicked campaign noted that the sheer volume of products risks oversaturation and consumer fatigue.

There’s also the danger of a “toxic partnership.” When Lexus partnered with The Weinstein Company, it was a sophisticated alignment of luxury brands—until the horrific Harvey Weinstein scandal broke, instantly tainting the carmaker by association.

More troubling is when marketing undermines the art. The campaign for It Ends With Us, a film about domestic violence, was widely condemned for its tone-deaf, “girls’ night out” promotion, trivializing its serious subject matter with floral pop-ups and glittery social media posts. It’s a stark reminder that when the marketing machine gets too powerful, it can crush the very message the film is trying to send.

Welcome to the Merch-iverse

Love it or hate it, the game has changed. The film is no longer the destination; it’s the invitation. It’s the launch party for a sprawling universe of clothes, toys, makeup, and even functional golf equipment that extends the story into our everyday lives. For franchises like Star Wars and Cars, merchandise revenue has lapped box office totals many times over, proving where the real money lies.

So next time you see a movie, remember you’re not just watching a story. You’re witnessing the birth of a brand empire. Welcome to the merch-iverse.

Want to dive deeper into the data and history behind this marketing revolution? You can find the full, in-depth report here.

👍