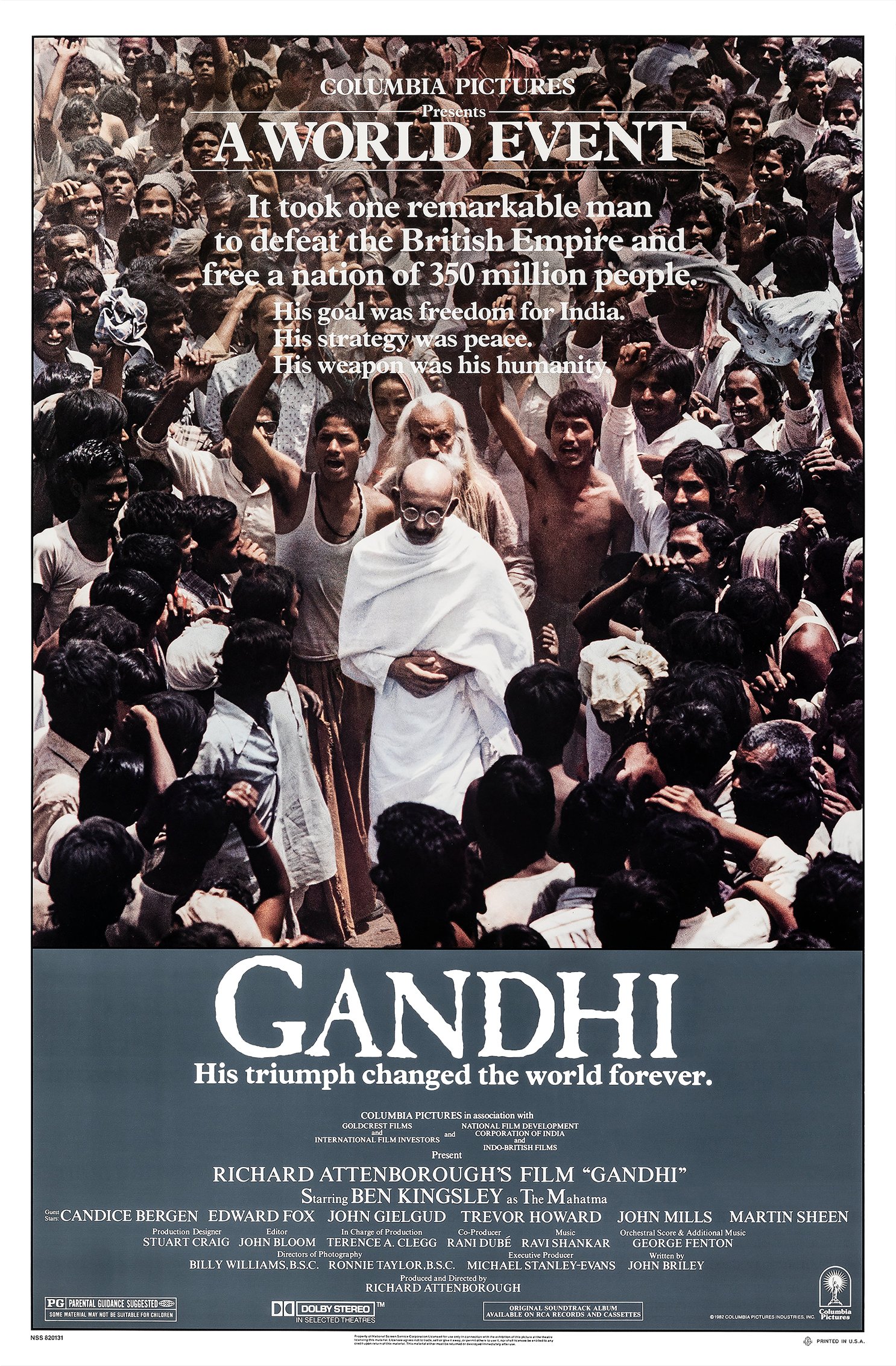

In the hallowed halls of cinematic history, few films stand as tall as Richard Attenborough’s 1982 epic, “Gandhi.” A sweeping, reverent, and visually stunning biopic, it garnered eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and a much-deserved Best Actor for Ben Kingsley’s transformative performance. For many, “Gandhi” was more than just a movie; it was a cultural event, a cinematic pilgrimage that introduced a generation to the life and philosophy of one of the 20th century’s most iconic figures. But as the dust of its initial acclaim has settled, and as the cultural landscape has shifted, a more complex and critical understanding of the film has emerged. In 2025, to watch “Gandhi” is to be confronted not only with a powerful piece of filmmaking but also with a web of controversies that have only grown more potent with time.

The Specter of “Brownface” and the Evolving Discourse of Representation

At the heart of “Gandhi”‘s complicated legacy lies the casting of Ben Kingsley. While Kingsley’s own Indian heritage (his father was of Gujarati descent, the same region as Gandhi) was a significant factor in his selection, the visible darkening of his skin to more closely resemble the Mahatma has been a persistent point of contention. In the 1980s, this was often defended as a necessary artistic choice for the sake of historical accuracy. Some even claimed that Kingsley’s tan was achieved through natural means. But in the 21st century, in the wake of movements like #OscarsSoWhite and a more nuanced understanding of racial representation, the practice of altering an actor’s skin tone, regardless of their heritage, is viewed with far greater scrutiny. The term “brownface” is no longer a fringe accusation but a mainstream concern, and “Gandhi,” for all its artistic merits, remains a prominent example.

The controversy is not merely about makeup; it’s about the very nature of storytelling and who gets to tell whose stories. While Kingsley’s performance is undeniably brilliant, the fact that a British-Indian actor was chosen for the role, and that his appearance was further altered to fit a specific image of “Indian-ness,” raises uncomfortable questions about authenticity and the lingering influence of colonial perspectives. In a 2025 context, where the call for authentic representation is louder than ever, the casting of “Gandhi” serves as a stark reminder of how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go.

The Saint and the Sinner: Deconstructing the Hagiography

Beyond the casting, “Gandhi” has faced significant criticism for its hagiographic portrayal of its subject. The film presents a sanitized, almost beatific version of Gandhi, a man seemingly without flaws or internal conflicts. While this makes for a powerful and inspiring narrative, it does a disservice to the complexity of the historical figure. The real Gandhi was a man of contradictions: a passionate advocate for non-violence who also held deeply problematic views on race, particularly during his time in South Africa. He was a champion of the oppressed who also had a troubled relationship with his own family, and whose views on caste were far from straightforward.

The film largely sidesteps these complexities, opting for a more straightforward, “great man” narrative. This is most evident in its depiction of Gandhi’s relationship with his wife, Kasturba. The film portrays their bond as a simple, supportive partnership, glossing over the more difficult aspects of their marriage, including Gandhi’s often domineering and controlling behavior. In 2025, where audiences are more attuned to the complexities of historical figures and more willing to engage with their flaws, the film’s one-dimensional portrayal of Gandhi feels both dated and dishonest.

The “Villain” and the “Extras”: The Problematic Portrayal of Others

The film’s hagiographic approach to Gandhi is mirrored in its simplistic portrayal of other historical figures. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the All-India Muslim League and the founder of Pakistan, is presented as a one-dimensional antagonist, a cold and calculating politician who stands in stark opposition to Gandhi’s moral purity. This not only distorts the historical record but also perpetuates a harmful and inaccurate narrative about the Partition of India, a complex and tragic event with a multitude of contributing factors. The film’s simplification misses the crucial irony that Gandhi, the primary architect of India’s independence, was the staunchest opponent of its division. The Partition was a confluence of factors: a hasty British exit, Jinnah’s unyielding demand for a Muslim homeland, and the reluctant agreement of Gandhi’s own allies in the Congress party who feared a catastrophic civil war. Politically isolated, Gandhi refused to celebrate independence and instead traveled to the epicenters of violence, using his moral authority and fasting to quell riots and protect minorities. It was this very work of reconciliation that led to his assassination by a Hindu extremist, a tragic culmination the film touches on but fails to fully contextualize.

Similarly, the Indian people are often reduced to a faceless mass, a backdrop for Gandhi’s heroic struggle. With the exception of a few key figures, the film rarely gives voice to the diverse and often conflicting perspectives of the Indian population. The focus remains squarely on Gandhi and his interactions with the British, reinforcing a colonial-era narrative that centers the white experience and relegates the colonized to the role of passive recipients of history. In 2025, in an era of postcolonial and decolonization movements, this narrative approach feels not only outdated but also deeply problematic.

The Enduring Power and Problematic Legacy of “Gandhi”

So, what is the legacy of “Gandhi” in 2025? It is a film that remains both a cinematic masterpiece and a cultural artifact, a powerful testament to the life of a remarkable man and a cautionary tale about the dangers of historical oversimplification. Its stunning visuals, sweeping score, and Kingsley’s tour-de-force performance continue to captivate audiences. But its problematic aspects, once whispered in the margins of film criticism, are now central to its understanding.

To watch “Gandhi” in 2025 is to engage in a critical dialogue with the past. It is to recognize that even the most well-intentioned films can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and historical inaccuracies. It is to understand that the stories we tell, and how we tell them, have real-world consequences. And it is to acknowledge that the work of decolonizing our minds and our media is an ongoing and essential process. “Gandhi” may no longer be the unassailable monument it once was, but it remains a vital and necessary text for anyone interested in the complex interplay of history, cinema, and popular culture.